April 1, 2003

Nashville, TN

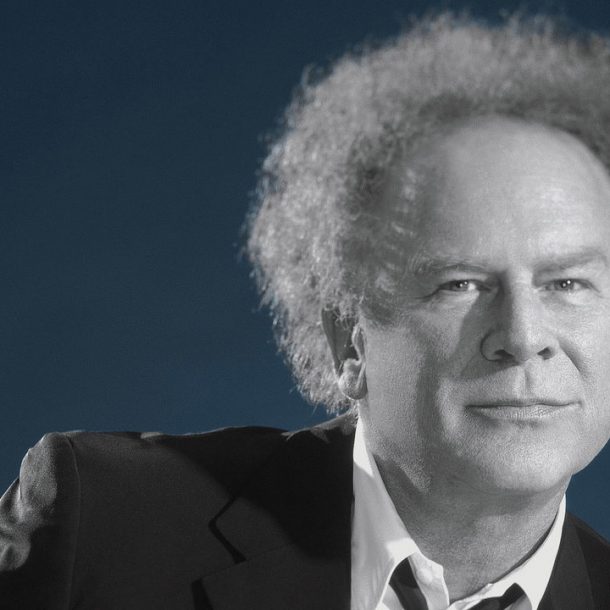

Ken Paulson: Welcome to a special edition of “Speaking Freely” at the Tin Pan South Festival here in Nashville. I’m Ken Paulson. Today we’ll take a look at a collaboration among three remarkable musicians. And the heart of the project is a legendary singer, actor, and poet. We are pleased to welcome Art Garfunkel. [Applause]

Art Garfunkel: Thank you so much. Thank you. I’m real happy to be here.

Paulson: Great to have you. I had the great pleasure of seeing you perform at Ellis Island.

Garfunkel: Oh.

Paulson: What a remarkable night. This was at the end of your walk across America.

Garfunkel: That’s right.

Paulson: And that walk took 14 years?

Garfunkel: Well, I did it in 40 different installments, always flying back to where I left off, so, between the mid-’80s and the mid-’90s, I crossed the continent — from my home in New York City to the Pacific.

Paulson: And then that led to the amazing night at Ellis Island, where you not only performed some of your greatest songs; you also reflected on your heritage.

Garfunkel: That’s right. I mean, Ellis Island is the gate where they came from Eastern Europe into Manhattan, and then most, most immigrants moved onto the continent. My family stayed in New York City, and I am the third generation of that lineage.

Paulson: I was struck, reading about the early days of Simon and Garfunkel — of course, you started as a rock ‘n’ roll duo, Tom and Jerry.

Garfunkel: We saw ourselves as children of the Everly Brothers. Rockabilly, we called it in those days.

Paulson: Well, here in Nashville, Tom and Jerry would be very big and should have been very big. “Hey Schoolgirl” was your first hit.

Garfunkel: In high school, in the ’50s.

Paulson: So, you were a co-writer, actually, in the beginning.

Garfunkel: Yeah.

Paulson: Although this new album that we’ll be talking about marks your return as a songwriter, you’ve actually been at it for a good few decades.

Garfunkel: That’s right. I mean, after our early high school days, when Paul Simon and I were writers of these Buddy Holly kind of country rock ‘n’ roll songs, then came the age of Bob Dylan, and Paul became this wonderful, first-rate, poetic writer, and I easily deferred to that talent through our whole famous career.

Paulson: I have to ask: Did you ever cross paths with the Everly Brothers?

Garfunkel: I saw Phil Everly outside the Brill building on Broadway in New York in the ’50s wearing a sharp black suit and boots with Cuban heels. And I knew who he was very well. He didn’t know me. He was looking for directions —

Paulson: [Laughs]

Garfunkel: — where to find a certain music building, and I had the honor of helping him find where he was going, and then I just retreated. That’s, that’s it.

Paulson: I gather he didn’t recognize you.

Garfunkel: Nope.

Paulson: Not from Tom and Jerry. What I found very interesting is the struggle you had. I mean, speaking of your heritage — once Tom and Jerry had disappeared and once Simon and Garfunkel had gotten back together again after Paul had been a solo performer for a little while in Britain — you had to decide whether you were going to be Simon and Garfunkel, and that was actually a discussion about whether that name was too ethnic.

Garfunkel: You bet. And we categorically rejected the name. It was — for us, it was definitely the absence of a name. And while we struggled to find a name, we failed, and, so, we went with our real names by default. And I can remember Tom Wilson, our producer at Columbia Records, saying, “Oh, hell. It’s ’65 —” meaning, “It’s such a modern era. Let’s go with their real names.”

Paulson: And because people would respond to Jewish names as being too ethnic and would not respond to the record — is that the idea?

Garfunkel: It sounded like a law firm. [Laughter]

Paulson: When you did enter the studio with Paul Simon, you put out an album that sold moderately well but didn’t ensure a success long-term. And, in fact, was there a time when you thought perhaps Simon and Garfunkel was a one-album project?

Garfunkel: Not even one. I mean, that first album of 1964 to ‘5 — Wednesday Morning, 3 a.m., which had “The Sound of Silence” in it — was not happening, and Paul went off to England and was a folk singer, and I went back to college, where I was an architecture student uptown at Columbia — until about a year later, when the record company was saying, “We’re getting a whole cult of call-ins in the Florida area around one of the titles on this folk album, and they just won’t quit. It’s like ‘Rocky Horror Picture Show’ [Laughter] and it’s ‘The Sound of Silence,’ and we think you should act on it because the fans are saying, ‘There’s something about this tune.’”

Paulson: But you added a little bit.

Garfunkel: So, as we were away in England, Tom Wilson put on an electric 12-string, the fashionable sound of that season — The Byrds and “Mr. Tambourine man” — and they added a drum and bass and superimposed on Paul’s guitar and our voices this sort of rock ‘n’ roll backing. And they played it for me when I got back for the summer, and I said, “Well, yeah, let it go.” I mean, I had no artistic integrity to stand on. I was a guy trying to get on the radio. [Laughter] And slowly, in that fall of ’65, it climbed, and I watched my life change. Every week, it — the ceiling of my world opened up further.

Paulson: And what a remarkable combination: Paul Simon’s writing, certainly, his voice, his guitar and your — what has been described as an angelic voice, a flawless voice. When did you know you had this gift? How old were you?

Garfunkel: Five.

Paulson: Really? [Laughter]

Garfunkel: As a very young kid, I saw I have something lucky going on here, and it behooves me to be serious about it and enjoy it, and don’t mess it up, and don’t scream. And I always like to say, because it’s my memory of grade school — kids would walk down the stairwell and walk home from school, and I would linger in the back because I fell in love with tiled stairwells. There’s the reverb that we singers love. Everybody who sings in the shower knows what I mean. And I’d stand, and I’d — the kids would go home, and I would sing “You’ll Never Walk Alone” or those goose-bump inspirational songs, and I would go, “I have some lucky thing going on here.”

Paulson: And Paul Simon reportedly saw you for the first time in the third grade?

Garfunkel: Yeah, third or fourth grade. I was the singer in the talent show. I was very blond. The girls liked me. [Laughter]

Paulson: Did Paul have a talent at that time?

Garfunkel: He says to me that’s when he realized singing is the ticket.

Paulson: Wow.

Garfunkel: And he’s — although I met him in the sixth grade, when I was an 11-year-old, he said, “I was laying for you for a couple years. I knew you were the kid in the neighborhood I wanted to know. And the reason why you thought I was so funny is because I was pitching to win you over with all my best material.” And since we were timed in our ages ideally to be smitten with rock ‘n’ roll — you know, Elvis came along just about the next year, when Paul and I were 12. So, this is something that McCartney knows and Dylan knows. We’re of that age to be just perfect to be hit with rock ‘n’ roll. And we began to start writing and singing together.

Paulson: You described the first moment you knew you had magic. When did you and Paul first harmonize?

Garfunkel: It’s hard to remember. We had home tape recorders. We were in love with the fun of recording into a tape recorder and setting up a second tape recorder, so, the playback of the first would be something we could sing to into the live mike of the second recording. So, we were building up sound on sound. And I guess right in the beginning, my ear said, “It’s very accurate,” and then I was — I’ve been a rehearsal freak all my life. I love to detail it until it’s, until it’s right. So, early in junior high school, we started having a pretty professional sound.

Paulson: As your career proceeded, Paul did most of the songwriting, but you had a hand in a lot of the creative process. You helped with the melody to “Scarborough Fair.” You also did something that is just haunting on Bookends. I understand you went into the nursing homes to record.

Garfunkel: Paul was working on a sequence of songs, making the whole side so that the songs would be unified. And the theme was birth to old age, and the spirit and the tempo of the songs would keep aging and getting slower and have more gravity. And when we knew we were going to end with a song about old people, we wanted to set it up with the sound of old people, live recordings of people, people doing what I’m doing — clearing the throat and sounding — and just having the back-of-the-throat sounds so you would have a visceral connection with the theme of the next song. And I did all these tape recordings, and we began to love the content of what they were saying, and we edited it down to set that up. But my real contribution beyond singing in those years was as record producer. I was the man behind the glass in the control room sending the vocals of Paul and Artie out on mike. And along with Paul and Roy Halee, we produced our records. So, if you want to know how I look at that whole career, from my point of view, we were not so much singers or writers, we were record-makers. The record-maker chooses the structure of the song, the tempo, picks the musicians who play, what the groove is, and, so, that’s what we controlled.

Paulson: Can you talk about the birth of one of your greatest songs, “Mrs. Robinson”?

Garfunkel: “Mrs. Robinson” came along when we were working with Mike Nichols on the film “The Graduate.” He had commissioned Paul to write three songs, and Paul wrote a song, which later became “Punky’s Dilemma,” for Dustin Hoffman floating in the pool, and Mike said, “Mm, I don’t know about that. What else you got?” And as he waited for Paul to write new things, he was living with our pre-existing songs, and he began to slot “Scarborough Fair” in this place, and “’Sound of Silence’ will go here,” waiting for the new songs, and he fell in love with those songs as was. So, he no longer needed anything, but he said, “Give me one new song for the chase scene when Dustin is running down from Berkeley back to L.A.,” and Paul was working on a song which at that time was called “Mrs. Roosevelt.” [Laughter] [Sings] “And here’s to you, Mrs. Roosevelt.” That’s how it went. So, I said to Mike, “Well, there is a song in the making called ‘Mrs. Roosevelt.’ I don’t think Paul likes it, and we’re about to chuck it.” And Paul said, [Clenches fist in grabbing motion] “Aaeer” — Mike jumped on it. And, so, we played it for Mike, and he said, “Well, how could we resist that? It’s perfect. Now you have to finish writing the song,” Which we never did until the film was out. That’s why in the film you hear, “Do, do-do-do, do-do.” [Laughter] There are no lyrics yet.

Paulson: I understand Joe DiMaggio had mixed feelings about “Where have you gone …?”

Garfunkel: Joe was a literalist. [Laughter] He didn’t appreciate the metaphor: “Where have you gone, that early, soulful America when heroes were heroes?”

Paulson: This show is about free expression and the way we express ourselves in America. I find it fascinating that some people were set on their heels by the line about Jesus — that a reference to Jesus in a popular song was something — “Jesus loves you more than you will know” — that that is something that would make people uneasy. Did — were you aware you were doing some groundbreaking there?

Garfunkel: No, never, actually. There are buzzwords that jump out of sentences, and it’s just the way we’re all made. Whatever is human just is. You can’t say anything.

Paulson: Well, you know, the Sinatra version, you’ve heard, of “Mrs. Robinson.”

Garfunkel: Yeah, what’s he say?

Paulson: He says, “Jilly loves you more than you will know.”

Garfunkel: Ah, there you go.

Paulson: His barkeeper friend Jilly — he substituted it. And I’m certain that Jilly was a far more controversial figure than Jesus. No matter where you lived.

Garfunkel: Paul wrote to the Sinatra people and said, “You can’t do that. That’s my song,” and the Sinatra people said, “We’re doing it.” [Laughter]

Paulson: So, over a period of time, you become the most successful — certainly the most successful duo in pop music history, and you get invited to do a television special your way with Bell Telephone.

Garfunkel: What a fascinating chapter that was.

Paulson: Can you talk about that process?

Garfunkel: Now you’re into the theme of the show, because that was a real confrontation with the powers that be in CBS. They were very nervous about the fact that we made an hour television special sponsored by Bell Telephone — this is as American as you can be — that had a humanist, political statement to it. And it had Coretta King saying, “I must remind you that starving a child is a form of violence.” And it had some teeth to it, and we were very proud. And the executives at Bell began to get nervous: “Are we being really universally embracing enough to all the stations, even — to all the stations?” And they called in the executives, and one by one, nobody could commit. They couldn’t decide what they felt about it, so, they would bring in the next-senior guy until the head guy would say, “We can’t abide by it. When you’re showing ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ — the first time we had aired it — “you’re showing the funeral of three Americans: Martin Luther King, Bobby Kennedy, and John Kennedy. They’re all Democrats. We can’t have that.” [Laughter] And we said, “I guess they’re all Democrats.” “Let’s face it,” they said, “you’re taking a political slant here.” And we said, “What’s the politics? It’s humanist.” And that’s the first time — if you’re humanist, you’re left of center, I guess. I thought humanity was the all and the everything. And we wouldn’t back down, and the sponsors pulled out just before airtime, and the networks went scrambling for a new sponsor at the last minute.

Paulson: And what happened?

Garfunkel: Alberto-Culver VO5 stepped in. [Laughter and applause]

Paulson: They’ve always been known for their radical leanings. And did that in any way affect the way you looked at future projects? I mean, any kind of chilling effect when people walk out on a program you’re proud of?

Garfunkel: Not really. There’s a very important element that goes on. When you’re selling a lot of records, you have a sense of personal power: “If they don’t like it, I’ll find someone else who will, because I have, I have clout. I have this important thing. I’m selling records, and I know there’ll be a lot of people on my side.” I suppose that, you know — earlier in this very interview, I was saying it — when they put out a record where they doctored it, I didn’t have any leg to stand on, and, so, you’re in a different, compromised position.

Paulson: We have to ask you about Bridge Over Troubled Water. This album was — I mean, for it to be your final album — that’s what’s so astonishing. So many bands have a peak moment, and it sells more copies than ever before, and then they have to put out five more just like it. And you guys went out at the crest. And “Bridge” itself is such a phenomenal song. Can you talk about the recording of that? Did you know that this was going to be a song you were going to sing for the rest of your life?

Garfunkel: Not quite, but I knew it was coming out very good, as I felt the whole album. You know, it may be delightful to hear it, but the first ears that hear one’s own work are one’s own ears, so, you’re your first spectator, and if it’s good, it’s — in layman’s terms, it’s a delight to hear it. And in the making of it, I can’t tell you what a thrill it is to play that studio game of crafting rhythm, melody, words, and engineering. And, ah, yes, I knew the whole album was turning out very good, and I felt, “This Paul Simon and I have some kind of lovely combination here along with Roy Halee.” The “Bridge Over Troubled Water” song itself was originally a two-verse song that Paul wrote without the final “Sail on, silver girl” verse. And he wrote it for me, and it was pitched in the high register, and when I recorded it, it came to me that this is not the song — this is the setup for an as-yet-not-written final verse. And I said, “Paul, let’s take the record now and lift it off the ground with a third verse. If you’ll write something that really goes from here, we’ll produce — we’ll bring in the kitchen sink. Step-by-step, we’ll bring in instruments, and the record will open up.” We were sort of influenced by Phil Spector’s production of the Righteous Brothers singing “Ol’ Man River,” which had impressed Paul and [me] a lot, in which Phil has Bill Medley singing the entire “Ol’ Man River” with just piano backing, and on the final line, [Sings] “Been sick of trying, but ol’ man” on that final line, he brings in the conga, the chorus, the girls singing, the rhythm. Everything breaks out. And we thought, “How cool to save production for the final line.” And, so, that production technique is a big part of what makes “Bridge Over Troubled Water” an unusual thing.

Paulson: You also have had a remarkable solo career. At a songwriters festival — I have to ask you — how did you make your way through a sea of songwriters and find the people you did — extraordinary talents like Jimmy Webb and Gallagher and Lyle, Albert Hammond? You — I guess because you’d worked with one of the best, you knew the best.

Garfunkel: Yeah, I have good taste, I think, and life is so much about what comes to you and what you’re aware enough to say “Yes” to. It’s — you know, when people ask, “How did you choose this acting career?” You know, the phone rings one day, and here comes an interesting offer, and you have to go, “I think this is good.” It’s the power of the editor. There’s the stream of everything coming at you, and what you choose or what you realize is worthwhile is the key.

Paulson: And you went back to several people. Jimmy Webb has been on virtually all your albums.

Garfunkel: I’m crazy about his writing. He came into our studio before Paul and I were finished working with each other, and I’d never met him. And he’s a charming Oklahoman. And he sat down, knees together, playing his piano style. He was his father’s church organist when he was a kid, and he played this great piano weaving style, and I was taken with him.

Paulson: You mentioned having a script shown to you. You’ve got a remarkable film career in that it’s relatively brief — you only do a movie every seven, eight years or so on average — and the movies you make, everybody talks about, beginning with “Catch-22” and then “Carnal Knowledge.” And you’re the first guest we’ve had who’s had a film taken to the U.S. Supreme Court. A city in Georgia declared “Carnal Knowledge,” which starred you and Jack Nicholson and Ann-Margret —

Garfunkel: And Candice Bergen.

Paulson: — and Candice Bergen. This film was declared obscene and could not be shown in Albany, Georgia. And that case was appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Were you surprised that this particular film generated so much controversy?

Garfunkel: Yeah. I don’t know what to say of that. You touch different people’s sensitivities, and you never know — if we use the theory of “Let’s be careful for everybody,” we water down anything that makes any statement out of too much care. We see that in the insurance business now: “The doctor can’t touch you because there’s a potential lawsuit,” and this flattens out any kind of intelligence. There’s a thing called too much safety and care.

Paulson: And from that experience, you were also in “Bad Timing.”

Garfunkel: Yeah, there’s a strong movie.

Paulson: That was a very powerful movie. Not a lot of people saw that. And “Boxing Helena” was not a musical either.

Garfunkel: [Laughs] Well said, Ken.

Paulson: You know, there’s, there’s —

Garfunkel: My game in my life is to stay interesting to myself, so, I keep looking to not repeat myself, to stay alive. What’s going to be a reach for me? What’s gonna get me a little scared? Because anything worth doing starts with that “I’m just the right amount of risky on this.”

Paulson: And that would define your films. You were never offered any of the “Brady Bunch” movies? [Laughter] That never came up?

Garfunkel: I did eschew the mainstream. I look at a script, and I go, “Why does this film want to be made? What’s the thrust of it?” And, so, many of them want to turn a profit, and that’s not quite good enough.

Paulson: Well, of course, it’s great to have the freedom to say, “This is something I’ll be proud of.”

Garfunkel: I have had a lucky life.

Paulson: One of the things I’ve been struck by seeing both you and Paul Simon separately in concert is how well these songs that were once sung by both of you powerfully, emotionally — they still work as individuals, and I’m not sure why. I don’t know how that’s possible.

Garfunkel: Ah, but what a tough time we had in the Grammy show just a month ago getting this lifetime achievement award, doing “The Sound of Silence,” and meshing our two different versions of “The Sound of Silence” together. I must tell you it was delightful working with Paul. Yeah, he was a sweetheart. But there were very specific problems with his way that he’s come to sing it, and mine, and how we monitor sound differently, and to hook that up and keep your grace was the devil’s business. [Laughter]

Paulson: Well, it worked. It worked beautifully.

Garfunkel: Thank you.

Paulson: And a great many people around the world were very glad to see the two of you together.

Garfunkel: Me, too.

Paulson: I wonder if we could prevail on you to do a song from the era.

Garfunkel: Sure. Let’s show ‘em “Kathy’s Song,” because I think of this as probably Paul’s most beautiful love song to this day. [Sings] “I hear the drizzle of the rain. / Like a memory, it falls, / soft and warm, continuing, / tapping on my roof and walls. / And from the shelter of my mind, / through the window of my eyes, / I gaze beyond the rain-drenched streets / to England, where my heart lies. / My mind’s distracted and diffused. / My thoughts are many miles away. / They lie with you when you’re asleep / and kiss you when you start your day. / And a song I was writing is left undone. / I don’t know why I spend my time / writing songs I can’t believe / with words that tear and strain to rhyme. / And, so, you see I have come to doubt / all that I once held as true. / I stand alone without beliefs. / The only truth I know is you. / And as I watch the drops of rain / weave their weary paths and die, / I know that I am like the rain. / There but for the grace of you go I.” [Applause]

Ken Paulson: Joining us now is a remarkable array of singers and songwriters. First up is Billy Mann. He’s written many country hits, and he is the man behind this new CD we’ll be talking about (called Everything Waits to be Noticed). Next up is Maia Sharp. Her brand-new album, her third CD, is called Maia Sharp. I can’t figure out why that wasn’t the first one, but we’ll hear about that. And, finally, Buddy Mondlock, also a tremendous talent, successful songwriter and artist in his own right. Great to have you here, and we’re here to talk about how all of you came together for this remarkable project. And I guess the guy who gets the credit first and foremost is Billy Mann.

Maia Sharp:All goes to Billy.

Paulson: Talk to us, will you, please, about how you brought these talents together? How did you know these folks would work well, and where did it all begin? [Laughter]

Billy Mann: Yeah. Well, as it started, I had met with some folks in New York who work with Artie and had asked me about thoughts about working with Artie and what he was up to and what my thoughts might be about him, and a little after that, I’d gone to London and done some songwriting there and worked with Graham Lyle, who wrote “Heart of New York” for Artie, among others. And he’s a wonderful human being and songwriter, and we wrote this song called “Bounce.” And when we wrote the song, I left thinking, “This is, this is the song I need to play for Artie. This is a way for us to get to know each other and begin.” And I went to his house, and I pulled up in a taxi, and we just hit it off. And when I was in Europe, around the same time, I went to London. Bob Doyle, who manages Buddy and myself, had played me some Buddy Mondlock songs, and they were just paintings. And I remember listening to them and thinking, “Hmm, this is an interesting combination for Artie.” And I had met Maia in France — God, this sounds so glamorous, all this traveling. [Laughter] But I had met her at a songwriters retreat, and I loved Maia. I loved her music, I loved her voice, and she just comes with a very three-dimensional identity in, in all of her songs and something so unique. And I just thought, “This is an interesting group of people,” and ultimately it was Artie who, first of all, had the, the wherewithal and the vision to open up to these songwriters that he hadn’t heard of that weren’t Jimmy Webb or Paul Simon or Graham Lyle. And, two, it was really a phone call I got from Artie, a very obscure message on a voice mail that was something like — and I’ll do a bad impression of you, but it was like, “Bill, it’s Artie.” Pause. “Buddy Mondlock is sublime. I am sitting under an oak tree, and the color yellow is shooting out at me, and isn’t Maia Sharp velvet?” Click. And that was, like, the end of the message. [Laughter and applause] So —

Paulson: And very few people do Art Garfunkel, so —

Art Garfunkel: You said Buddy was a painting.

Paulson: Maia, do you recall your reaction when you got the phone call: “Would you like to work with Art Garfunkel?”

Sharp: Absolutely. It was around the holidays of 2000, I believe, and it sounded like a wonderful idea. I was on board, of course. I didn’t completely believe that it was actually gonna happen. [Laughter] I got to say, he followed through. He did everything he said that he was gonna do: “We’re gonna meet; we’re gonna write in Nashville; we’re gonna record at the end of that week; and then we’re gonna hook up in New York, and we’re gonna write for a week; and we’re gonna record at the end of that week, and then we’re all gonna fly out to L.A., and we’re gonna write.” And it happened. It was great.

Paulson: Buddy, what was your reaction when you got the call?

Buddy Mondlock: Well, I didn’t think it was — I thought Billy was joking with me, basically, [Laughter] because, you know, I’d been listening to Simon and Garfunkel records since I first picked up my guitar, so, the possibility of working with Artie was an amazing thing to think about for me. I thought, “Well, you know, whatever happens, you know.” Like Maia, I thought, “Well, whether I just get to meet — even if I just get to meet him would be great, but we’ll see where it goes from there. Maybe he’ll record one of my songs or something.” But —

Garfunkel: I have to leave the room. This is too embarrassing. [Laughter]

Paulson: We — the wild card, though, in this was that Art Garfunkel was a writer in this mix, which has not happened since Tom and Jerry, actually. And this is your book of poetry, Still Water, from 1989 —

Garfunkel: Yeah.

Paulson: — but still available. And wonderful reading, but I have to tell you — reading through this, if you had told me, “This is gonna inspire some songs,” I would say, “I’m not sure.”

Garfunkel: Me, too.

Paulson: This is, this is. I mean because —

Garfunkel: It’s not easy until these two came along.

Paulson: That’s right. “Konstantin Chernenko is dead. I am the newsman in any bedroom.” I don’t hear that on the album. [Laughter] I haven’t heard that. But it’s very striking stuff, but I don’t hear song lyrics, because it’s a dense —

Garfunkel: As poems are denser than songs. They’re different animals, and in my attempt to try and go from prose poem writer to songwriter, I had str — I struck out until Buddy took one of my poems and said, “Let me really try and transfuse it” with his friend Pierce Pettis. And he did it.

Paulson: Well, I’m sure a good many people in the audience have already heard “Bounce,” which has been very audible on the radio, and I’m sure many more songs will receive airplay all over this country — all over the world. You’ve been touring.

Garfunkel: Yeah.

Paulson: Where have you been?

Garfunkel: We’ve just done 17 shows in Germany, Austria, Ireland, and England. We had the great fun of playing the Royal Albert Hall two weeks ago. Thrill.

Paulson: And how do you mix your material with the new material from the CD?

Garfunkel: Something like half and half. I don’t want to lean on the past too much, even though it’s so much fun to do “Kathy’s Song” with Tab. So, you try and keep the proportions right, and I live in the present tense, but I don’t want to be coy and deny “Bridge over Troubled Water” to an audience or deny myself the fun of it.

Paulson: Well, you live in the present, and we should listen to the present. Could we hear some songs from this new CD?

Garfunkel: Sure.

Paulson: I’ll get out of the way.

Mann: I think I will too.

Sharp: You’re gonna be back, right?

Mann: I’ll be back.

Mondlock: Well, this is the song that we were talking about a second ago, kind of the first one that was written for the project. And this started as a poem that Art wrote, but it became other things too. [Plays and sings with Art Garfunkel and Maia Sharp] “I met you once before / the first time. / Cinema one or two, / I noticed you / standing in line. / Your eyes met mine, / and I could not look away. / There we were / in a perfect moment, / a perfect moment in time. / For a moment, you were mine. / So, later on, I knew the first time / that it would be all right for us that night. / Just in our eyes, we made a bridge of sighs. / When we crossed over, it was day. / There we were / in a perfect moment, / a perfect moment in time. / For a moment, you were mine. / I wasn’t ready for the last time. / But wasn’t I supposed to let you go / into the blue? / But still I’m holding you / though you’re a million miles away. / There we are / in a perfect moment, / a perfect moment in time. / For a moment, you are mine. / In a perfect moment, / a perfect moment in time. / For a moment, you were mine. / For a moment, you are mine. / Just for a moment, you are mine.” [Applause]

Garfunkel: It goes, “You are mine.”

Mondlock: [Plays and sings with Art Garfunkel and Maia Sharp] “Everything waits to be noticed. / A tree falls with no one there, / the full potential of a love affair. / Everything waits to be noticed. / Twenty-eight geese in sudden flight, / the last star on the edge of the night, / a single button come undone, / the middle child, the prodigal son. / Everything waits to be noticed. / A trickle underneath a dam, / the missing line from a telegram. / Everything waits to be noticed. / The whispering pains that say you’re living, / the slow burn of not forgiving, / the quiet room, the unlikely pair, / the full potential of a love affair. / Everything waits to be noticed. / Ooh, ooh. / Ooh, ooh. / Ooh, ooh. / Ooh. / Longing for braver days, / cautiously turning a phrase. / Going unnoticed. / But everything wants to be noticed. / Changing light in the upper air, / the full potential of a love affair. / Everything waits to be noticed. / Hoo, mm. / Hmm, mm.” [Applause]

Garfunkel: [Sings with Maia Sharp and Buddy Mondlock, playing] “I’m the kid who ran away with the circus. / Now I’m watering elephants. / But I sometimes lie awake in the sawdust / dreaming I’m in a suit of light. / Late at night in the empty big top, / I’m all alone on the high wire. / ‘Look, he’s working without a net this time. / He’s a real death-defier.’ / I’m the kid who always looked out the window, / failing tests in geography. / But I’ve seen things / far beyond just the school yard — / distant shores of exotic lands. / There the spires of the Turkish empire. / It’s six months since we made landfall. / Riding low with the spice of India / through Gibraltar, / we’re rich men all. / I’m the kid who / thought we’d someday be lovers, / always held out that time would tell. / But time was talking. / I guess I just wasn’t listening. / No surprise, if you know me well. / And as we’re walking toward the train station, / there’s a whispering rainfall. / Across the boulevard, / you slip your hand in mine. / In the distance: the train call. / I’m the kid who has this habit of dreaming. / Sometimes gets me in trouble, too. / But the truth is, / I could no more stop dreaming / than I could make them all come true.” [Applause]

Garfunkel: Some call him a visionary. Some call him a leader. I call him the troublemaker. [Billy Mann laughs]

Sharp: And this is the very song you played for Art over the phone, yes?

Garfunkel: This is what hooked me, Billy.

Mann: Thank you. [Plays and sings with Art Garfunkel, Maia Sharp and Buddy Mondlock] “Spin that wheel. / Just let go. / Where she falls, / nobody knows. / Save your breath. / Let those snake eyes roll. / We bounce between the devil and the deep blue sea, / bounce between forever and what may never be. / Let the light of love keep bouncing off the diamond / in the darker side of me. / I never had no education, / just an inarticulation of the heart. / But burning deep inside me is a diamond in the dark. / Catch that flame. / Let it warm your soul. / Love’s cruel game is the great unknown. / All that fear — / do you know you’re not alone? / We bounce between the devil and the deep blue sea, / bounce between forever and what may never be. / We bounce between decision, destinations constantly. / Let the light of love keep bouncing off the diamond in the darker side of me. / I never had no education, / just an inarticulation of the heart. / But burning deep inside me is a diamond in the dark. / A shine of flash, and then it’s over. / A lightning strike, a chance remark. / Am I the only one here like a diamond in the dark, / like a diamond in the dark? / ” [Applause]

” We walked through the station. / You ran and made the train. / I just got caught up in the crowd. / You turned back. / Our eyes met. / You could have sworn I was right behind. / Fear kept my feet flat on the ground. / Then you vanished with a smile, vanished with a smile, / like you knew that I would be awhile. / How did you know? / How did you know? / How could you tell? / How could you tell / that one day I’d love you completely? / Love you completely. / Now we can run, / Now we can run. / Into the night. / How did you know / that we were meant to be? / How’d you know to wait for me? / How’d you know to wait for me? / How’d you know to wait for me? / How did you know this? / How’d you know to wait for me?” [Applause]

© 2025 Art Garfunkel – Concept by Institut für Internetmarketing